It’s Monday morning, and you’re sitting in a high-production corporate training session. The slides are polished, the speaker is charismatic, and the coffee is expensive. You nod along, feeling like you’re absorbing every word. But by Thursday, if someone asked you to explain the three core pillars of the strategy presented, you’d likely offer a blank stare.

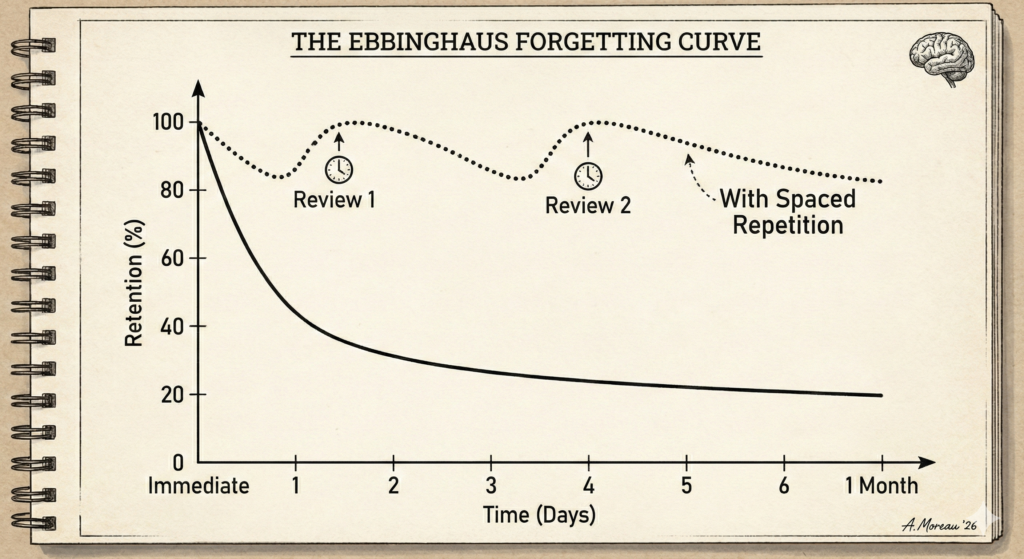

This is the “Forgetting Curve” in action, and in our hyper-distracted 2026 landscape, it has become a cliff.

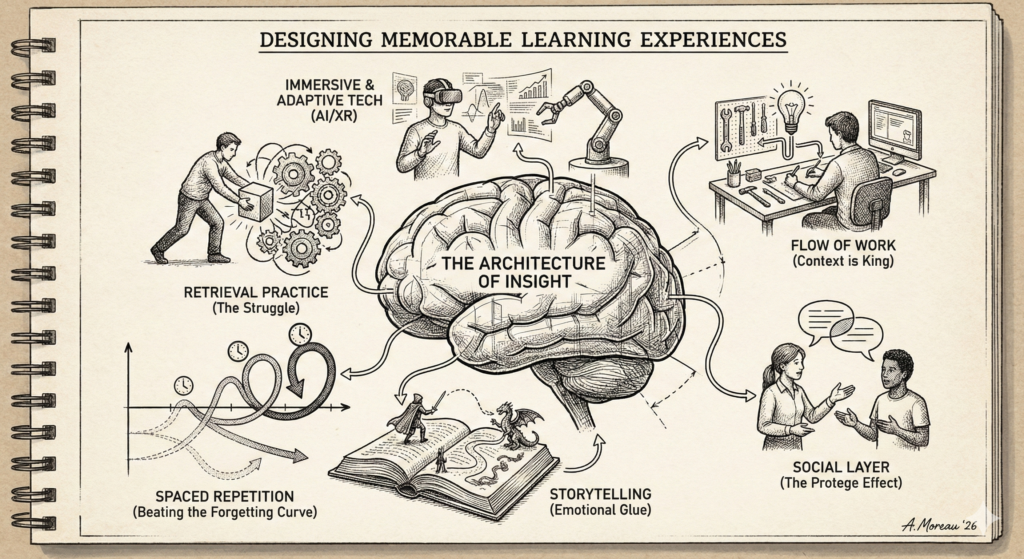

For decades, we approached learning as a delivery problem: If we provide the right content, they will learn. But in an era of infinite information and AI-curated feeds, content is no longer the bottleneck. The bottleneck is human biology. To create learning experiences that people truly remember, we have to stop being “content providers” and start being Experience Architects. We must move beyond the transmission of facts and begin engineering moments of insight. Here is the blueprint for designing learning that defies the forgetting curve.

1. The Neurobiology of the Narrative: Why Stories are “Stickier” Than Facts

If you want someone to remember a statistic, tell them a story. It sounds like a cliché, but the science of 2026 backs this up with startling clarity. When we hear a dry presentation, the language-processing parts of our brain (Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas) light up. We understand the words, but we don’t feel them.

However, when we are told a story, the entire brain joins the party. Our sensory cortex mimics the experiences described. If the protagonist is running, our motor cortex fires. If they are smelling a rose, our olfactory cortex activates. This interaction is called neural coupling.

The “Chemical Cocktail” of Memory

A well-told story releases a specific sequence of neurotransmitters that act as “emotional glue” for the brain:

- Cortisol: Triggered by the story’s “hook” or conflict, it focuses our attention.

- Oxytocin: Triggered by relatable characters, it builds empathy and makes the information feel personally relevant.

- Dopamine: Released during the resolution or “aha!” moment, it rewards the brain and signals that this information is worth storing for the long term.

The Architect’s Move: Don’t start with “Today we are learning about X.” Start with a protagonist, a high-stakes conflict, and a failed attempt. Force the learner to care about the outcome before you give them the tools to achieve it.

2. Engineering the “Struggle”: The Power of Retrieval Practice

One of the biggest myths in education is that “easy” learning is “good” learning. When a student breezes through a module, they often experience a “fluency illusion”—the mistaken belief that because the material is easy to read, it has been learned.

The reality? Long-term memory is built through desirable difficulties.

The “Push” vs. The “Pull”

Most training is a “push” system—we push information into the learner’s brain. Memorable learning is a “pull” system. It requires Retrieval Practice. Instead of asking a learner to review their notes, we must ask them to produce the answer from scratch. Every time a learner struggles to recall a piece of information, they are thickening the neural pathway to that memory. In 2026, we utilise “low-stakes” friction—quizzes that don’t grade you but challenge you; “brain dumps” where you write everything you remember on a blank screen; and “peer-teaching” simulations.

The Spacing Effect

The brain is not a bucket you can fill in one go; it’s more like a muscle that needs recovery time to grow. This is why “cramming” fails. To make learning stick, we use Spaced Repetition.

The mathematical formula for retrievability ($R = e^{-t/S}$) tells us that we need to hit the brain with a concept just as it’s about to forget it. By spreading learning over days or weeks—rather than one four-hour “PowerPoint marathon”—we allow the brain to engage in Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) during sleep, physically weaving the new knowledge into the existing neural web.

3. The “Goldilocks Zone” of AI and Immersive Reality

In 2026, the most effective learning experiences leverage technology not just for “wow factor”, but for hyper-personalisation.

Adaptive Difficulty

Using AI-driven tutors, we can now keep every learner in the “Goldilocks Zone” (formally known as the Zone of Proximal Development). If a task is too easy, the learner disengages; if it’s too hard, they experience “cognitive shutdown” and anxiety.

AI now monitors biometric feedback—heart rate variability and even gaze tracking—to adjust the difficulty of a simulation in real time. If the system detects frustration, it provides a “scaffold” or a hint. If it detects boredom, it injects a new challenge. This ensures the learner is always operating at the edge of their ability—the precise place where the most durable memories are formed.

Immersive Embodiment (XR)

Virtual and augmented reality have moved from novelty to necessity. Why? Because the brain struggles to distinguish between a vivid simulation and reality. When you practise a difficult conversation with an AI-driven avatar in VR, your brain records it as a “lived experience” rather than a “theoretical lesson.” This builds muscle memory and “affective memory,” which are far harder to lose than “declarative memory” (facts).

4. Context is King: Learning in the Flow of Work (LIFOW)

The most memorable things we learn are the things we needed to know ten seconds ago. Traditional learning is “Just-in-Case”—we learn things we might need one day. This is a recipe for forgetting. The future of learning is “Just-in-Time.”

The Survival Mechanism

The brain is an energy-saving organ. It is constantly looking for reasons to delete information to save calories. If you learn a software shortcut and then don’t use it for three weeks, your brain deletes it as “noise.”

However, if you are in the middle of a high-pressure project and a “smart nudge” (via Slack, Teams, or an AR overlay) shows you that exact shortcut, the brain tags it as a survival tool. It is immediately integrated into your workflow.

To make learning stick, we must shrink the gap between learning and doing to zero. We call this “contextual relevance.” If the learner can’t use the information within 24 hours, the experience architect has failed.

5. The Social Layer: We Learn to Teach

Finally, we must recognize that humans are inherently social animals. Our memories are deeply tied to our status and relationships within a group.

One of the most effective ways to solidify a memory is the Protege Effect: the phenomenon where people learn better when they know they have to teach the material to someone else. When we prepare to teach, our brains organize information more logically and identify gaps in our own understanding.

In the most memorable modern learning experiences, “students” are quickly transitioned into “mentors.” By creating social loops where learners must explain, defend, and debate their insights with peers, we move the knowledge from a passive state to an active, social state.

Conclusion: Becoming the Architect

Creating a memorable learning experience in 2026 isn’t about the size of your budget; it’s about the depth of your empathy for the learner’s biological constraints.

To build an experience that lasts, you must:

- Wrap it in a story to engage the emotions.

- Make it hard (but not too hard) to trigger retrieval.

- Space it out to allow for biological consolidation.

- Make it real through immersive technology and AI.

- Make it useful by placing it directly in the flow of work.

We are no longer in the business of information transfer. We are in the business of transformation. When we design with the brain in mind, we don’t just help people remember—we help them evolve.

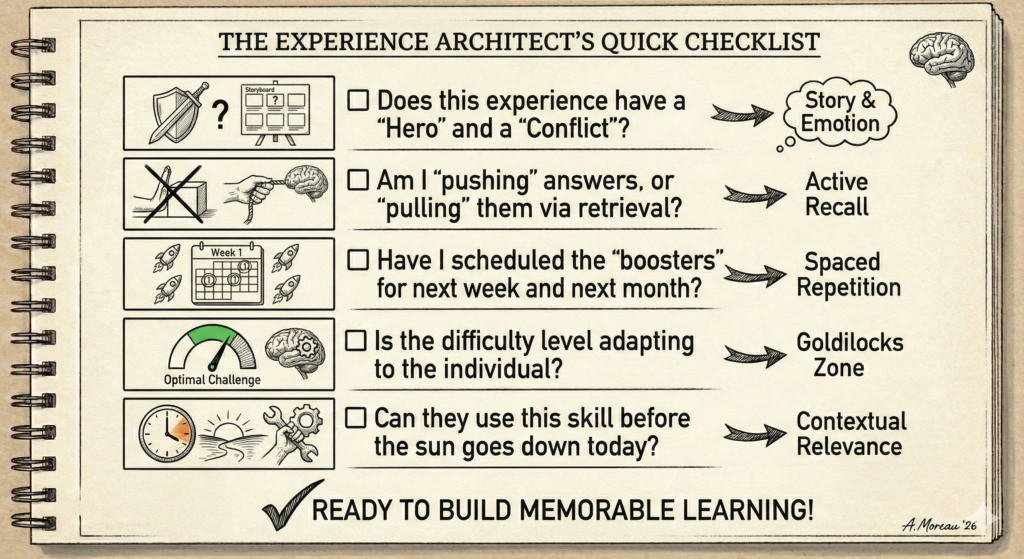

The Experience Architect’s Quick Checklist: